Groq backer Alex Davis warns of AI data center 'trap' and 2027 financing crisis

Fresh off a $20 billion Nvidia deal, the Disruptive Capital CEO predicts a reckoning for speculative landlords as hyperscalers embrace vertical integration.

In the high-stakes poker game of artificial intelligence infrastructure, Alex Davis just cashed in his chips. Now, he is warning the rest of the table that the house is about to lock the doors.

Davis, the CEO of Disruptive Capital, finds himself in a rare position of validated foresight. His firm led the funding for AI chipmaker Groq, a bet that paid off spectacularly this month when Nvidia agreed to a $20 billion asset and licensing deal for the startup’s technology. But while the ink is still drying on the semiconductor windfall, Davis is issuing a stark “red alert” regarding the physical concrete and steel of the AI revolution: data centers.

His warning to investors — that “build it and they will come” strategy for data centers is a “trap” — signals a critical pivot in the AI economy. It suggests the market is moving from a frantic land-grab phase into a period of ruthless vertical integration, where “hyperscalers” (Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon) squeeze out speculative middlemen.

Pivot From Chips to Bricks

The timing of Davis’s letter is as significant as its content. Coming immediately after the Groq-Nvidia transaction, the critique carries the weight of an insider who has successfully navigated the hardware cycle.

Davis is effectively calling the top on “dumb” infrastructure (real estate) while validating “smart” infrastructure (proprietary silicon).

”If you are a hyperscaler, you will own your own data centers,” Davis wrote in the letter to limited partners obtained by Axios. “We foresee a significant financing crisis in 2027–2028 for speculative landlords.”

This statement strikes at the heart of the current investment thesis for Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) and private equity firms pouring billions into server farms.

The assumption has been that demand for AI compute is infinite, therefore demand for rack space must be infinite. Davis argues this conflates compute demand with rental demand.

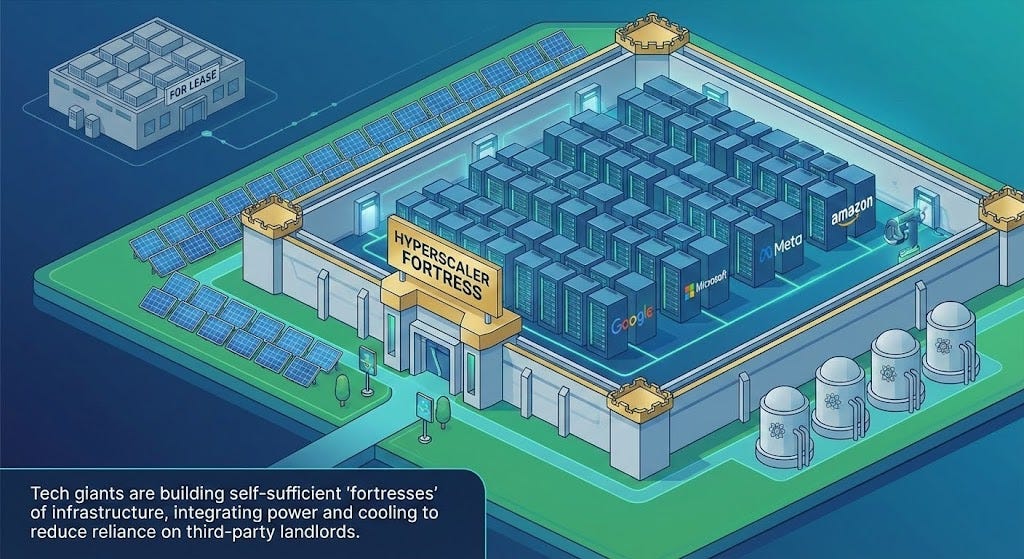

Hyperscaler Fortress Strategy

The core of the analytical argument rests on the changing behavior of the industry’s titans.

In the early 2020s, hyperscalers leased capacity to deploy quickly. Speed was the only metric that mattered in the race to train Large Language Models (LLMs).

But as the market matures in late 2025, the economics are shifting. Faced with massive capital expenditure requirements, Big Tech is shifting to ownership to control costs and, crucially, power topology.

This creates a “Hyperscaler Fortress” dynamic.

The largest tech companies are increasingly viewing their physical plant not as a utility to be outsourced, but as a proprietary competitive advantage.

They are building closed-loop systems where the chip, the server, the cooling, the building, and the power source are all integrated.

Davis’s warning highlights the “speculative mismatch.” Developers are currently building generic data centers hoping to lease them to Microsoft or OpenAI.

AI workloads, however, increasingly require bespoke cooling, power, and networking architectures.

A generic shell built by a speculative landlord effectively becomes a stranded asset; it cannot meet the extreme density requirements of next-generation clusters without expensive retrofitting that destroys the landlord’s margin.

Power Politics

Perhaps the most potent element of Davis’s critique is the recognition of physical limits. He notes that data centers are becoming “political flashpoints” due to electricity prices.

This introduces a geopolitical dimension to what was previously a commercial real estate transaction.

Hyperscalers are better equipped to negotiate gigawatt-scale power purchase agreements (PPAs) with utility providers or invest directly in nuclear Small Modular Reactors (SMRs).

The International Energy Agency’s 2025 outlook recently highlighted that skyrocketing data center demand is already outpacing grid capacity, creating a scenario where only the most politically connected players can secure power.

The speculative landlord, lacking these geopolitical connections and balance sheets, finds themselves with a building they cannot power.

When a data center consumes as much power as a mid-sized city, the entity that controls the electrons controls the market.

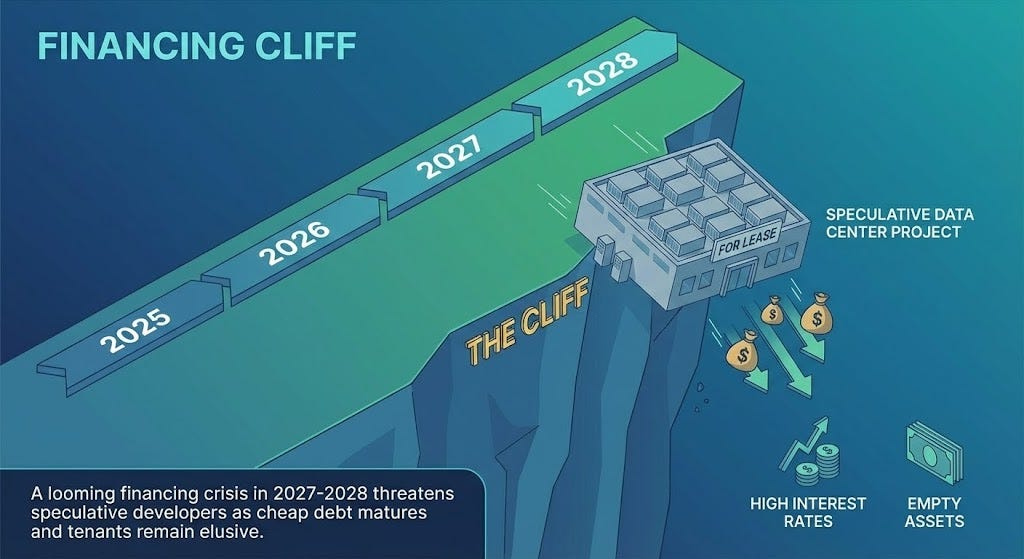

2027 Financing Cliff

Davis predicts a “significant financing crisis in 2027–2028.” This timeline is not arbitrary; it aligns with the maturity walls of the cheap debt raised during the early AI boom.

The mechanism of this potential crisis is classic bubble economics. Speculative projects funded by floating-rate debt or short-term bridge loans will need to refinance in that window.

If they haven’t secured a Tier-1 tenant because those tenants decided to build their own facilities, the landlords will be left with empty assets, high interest rates, and no revenue.

This threatens to create a “shadow inventory” of data centers. Much like the office real estate crash of the early 2020s, the data center market risks an oversupply of “Class B” inventory — facilities that are slightly too old, too far from fiber backbones, or too power-constrained to host cutting-edge AI training runs.

Context: The Portfolio Validation

To understand why Davis’s voice carries weight, one must examine his broader portfolio. Beyond Groq, Disruptive Capital has backed unicorns like Reflection AI, which focuses on autonomous coding agents, and Shield AI.

The Groq deal specifically validates Davis’s thesis: value accrues to unique intellectual property and the service layer, not necessarily the commodity middle. By selling the “brains” of Groq to Nvidia while the market was hot, Disruptive Capital capitalized on the consolidation phase of chips. By warning against data centers now, he is seemingly shorting the consolidation phase of real estate.

End of Passive Rent

For the broader market, Davis’s letter is a signal that the “easy money” phase of AI infrastructure is over.

The “trap” he describes is a classic asset-liability mismatch: building long-duration assets (data centers) for a technology cycle (AI models) that changes every six months. If the hyperscalers decide they need to own the dirt to control the power, the speculative landlord becomes an obsolete relic of the 2024 boom.

Ultimately, Davis is outlining the end of the “rentier” model in AI. In a world of scarcity — scarcity of power, scarcity of chips, and scarcity of talent — the entities that own the means of production will not pay rent to those who merely own the building. They will build their own cathedrals.