SAVE Act: Unintended consequences of voters' documentary proof

Data analysis shows 80% of deep-red voters lack passports, while 69 million women face name-mismatch hurdles. Is the cost of this new bureaucracy worth the risk to the 2026 map?

In the high-stakes theater of American election law, the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility (SAVE) Act (H.R. 22) has moved from a legislative proposal to the central nervous system of the 2026 midterm strategy.

While the bill is messaged on cable news as a common-sense shield for election integrity — a legislative fortification of the victory secured by President Donald Trump in 2024 — a granular analysis of its mechanics reveals a starkly different reality.

To the viewers of Fox News, the message is clear: “Secure the vote, stop the fraud.” But a deep-dive into the bill’s operational mandates reveals that the SAVE Act does target the “illegal” voters that pundits rail against.It also, however, constructs a massive, bureaucratic administrative tax that falls hardest on the very people who built the MAGA movement: rural families, married women and military veterans.

As the 119th Congress pushes to codify these standards ahead of the midterms, the data suggests that the Republican Party is inadvertently building a wall between its own base and the ballot box. The transition from a “signature-attestation” model to a “documentary proof” model — requiring physical passports or birth certificates — could create a bureaucratic bottleneck in rural America, disenfranchise millions of married women, and upend the logistical advantages currently held by Republicans in “red states.”

From oath to proof, a documentary shift

For three decades, the American voter registration system has operated on a principle of “attestation under penalty of perjury.” Established by the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (NVRA) — often called “Motor Voter” — this system allowed eligible citizens to register by signing a form declaring their citizenship. Lying on this form is a federal felony, a deterrent that has kept non-citizen voting rates infinitesimally low.

The SAVE Act seeks to dismantle this framework.

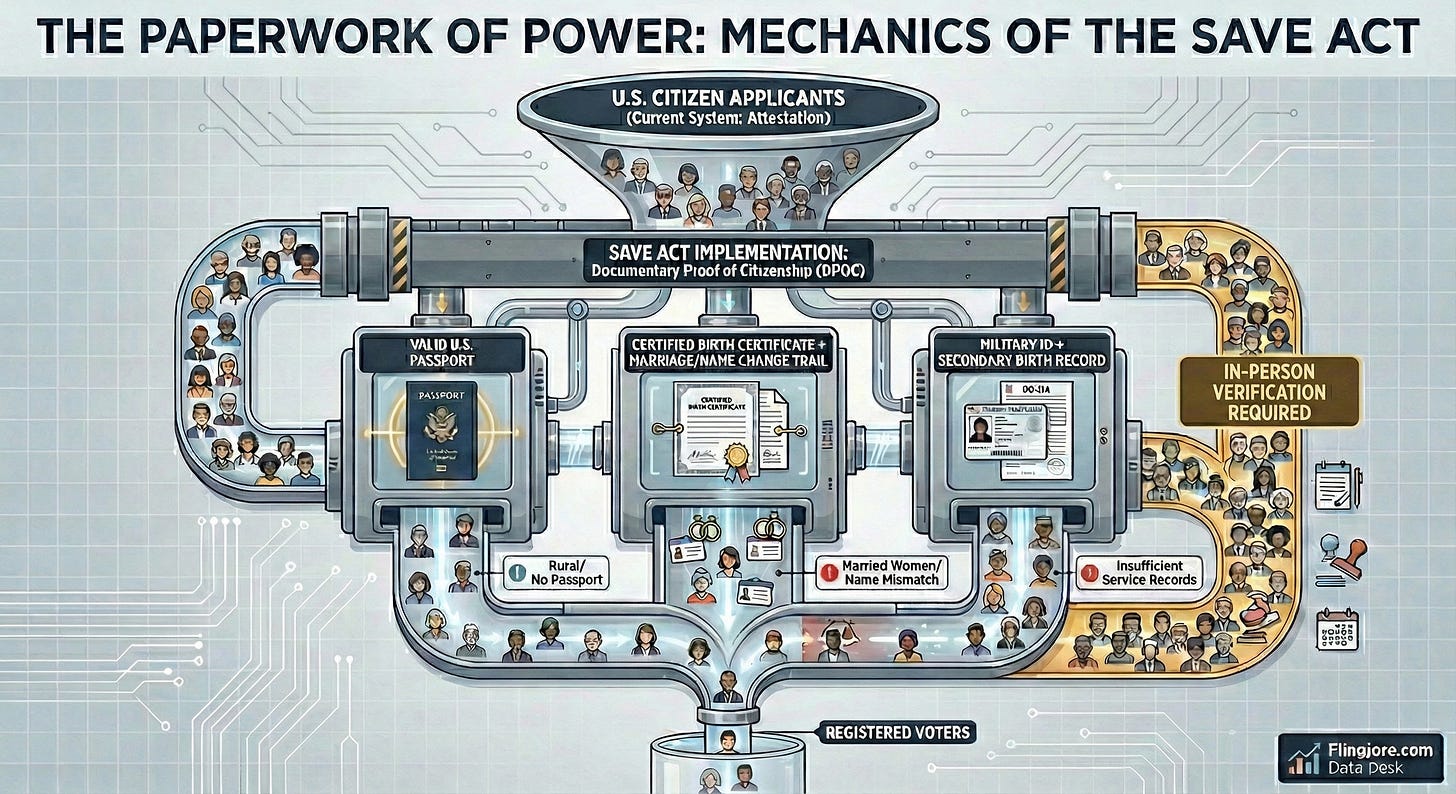

If fully enacted, it mandates that every citizen provide Documentary Proof of Citizenship (DPOC) at the time of registration. Many states are expected to require re-registration to fill new rolls and systems that are “corrupt.”

According to a Bipartisan Policy Center analysis, this shift moves the burden of proof from the government’s databases onto the individual citizen.

The list of acceptable documents is specific, rigorous and for many Americans, elusive:

A valid U.S. Passport or Passport Card.

A certified U.S. Birth Certificate featuring a raised seal (photocopies are inadmissible).

A Naturalization Certificate or Consular Report of Birth Abroad.

A Military ID — but only if it is paired with a secondary official record that explicitly confirms a U.S. location of birth.

Crucially, the bill effectively eliminates the convenience of the modern registration system. Because these documents must be verified for authenticity, the era of purely online registration or simple mail-in postcards for new voters comes to an abrupt halt.

In its place rises a system of in-person verification that demands time, travel and organization — resources that are often scarce in working-class communities.

Passport disparity is a ‘red state’ disadvantage

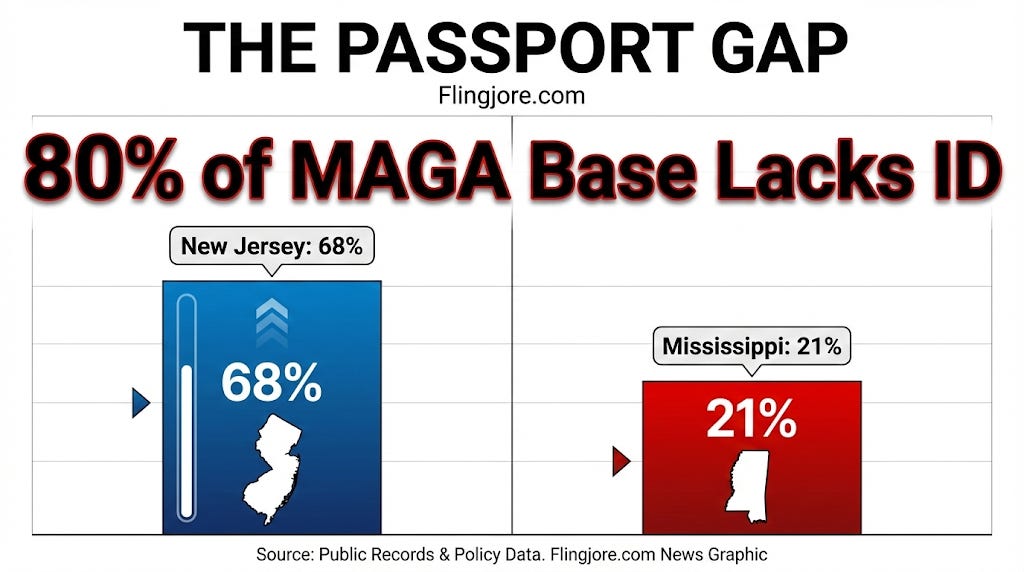

The most immediate hurdle is passport ownership. In the context of the SAVE Act, a passport is the “golden ticket” because it serves as both a photo ID and definitive proof of citizenship.

Data from the Center for American Progress and State Department issuance records show, however, that passport ownership is a luxury concentrated in the urban, high-income “blue states” that did not vote for Donald Trump in the 2024 presidential election.

In New Jersey, approximately 68% of citizens possess a valid passport — the highest rate in the nation. In Massachusetts and New York, the numbers are similarly high.

These are populations that travel internationally, work in global industries, and live in dense urban corridors with easy access to government services. In contrast, in the deep-red states that form the core of the MAGA movement, the numbers plummet.

Mississippi: ~21%

West Virginia: ~21%

Alabama: ~30%

Kentucky: ~32%

This “Passport Gap” creates a massive disparity in compliance friction.

For the 70-80% of citizens in these historically Republican strongholds who lack a passport, the SAVE Act requires them to locate a certified birth certificate.

For many working-class voters, replacing a lost birth certificate involves a bureaucratic scavenger hunt: filling out notarized forms, paying fees between $25 and $60, and waiting up to 10 weeks for processing.

In a midterm cycle where turnout is historically lower than in presidential years, placing a ten-week, sixty-dollar hurdle in front of a low-propensity voter is a strategic gamble with high risks.

Pennsylvania at a glance

To understand the political peril of the SAVE Act, one must look at Pennsylvania, the state that effectively decided the 2024 election. President Trump flipped the state back to the GOP column by a margin of just 1.7%, driven by surging turnout in rural counties and a dampening of Democratic enthusiasm in the cities.

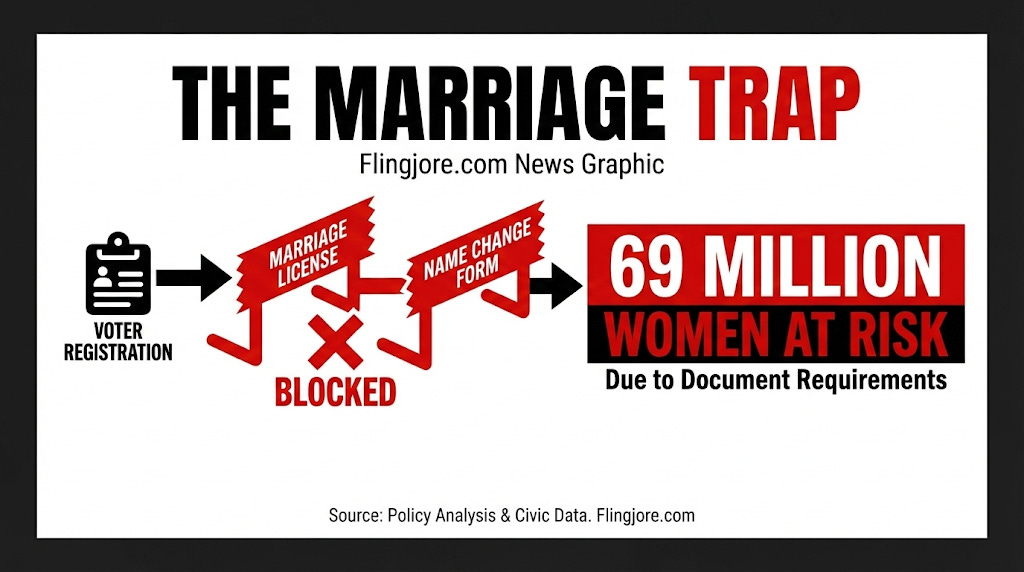

In Bucks County, a critical swing area north of Philadelphia, the electorate is a mix of affluent suburbanites and working-class tradespeople. Here, the “Marriage Trap” becomes a potent mathematical spoiler. The Brennan Center for Justice estimates that 69 million American women do not have a birth certificate that matches their current legal name due to marriage.

In a county like Bucks, where the GOP relies on the support of “security moms” and suburban families, the requirement to produce a paper trail of marriage licenses to link a birth name to a voter registration could cause chaos.

If a voter named Jane Marie Smith shows up with a driver’s license reading Jane Smith but a birth certificate reading Jane Marie Doe, the SAVE Act mandates that she produce her marriage license. If she has been married more than once, she needs the divorce decrees and subsequent licenses to prove the entire chain of custody of her name.

For a busy suburban mother, this is a bureaucracy tax that her single, male counterpart does not pay.

The Rural Wall: Tioga and Potter Counties

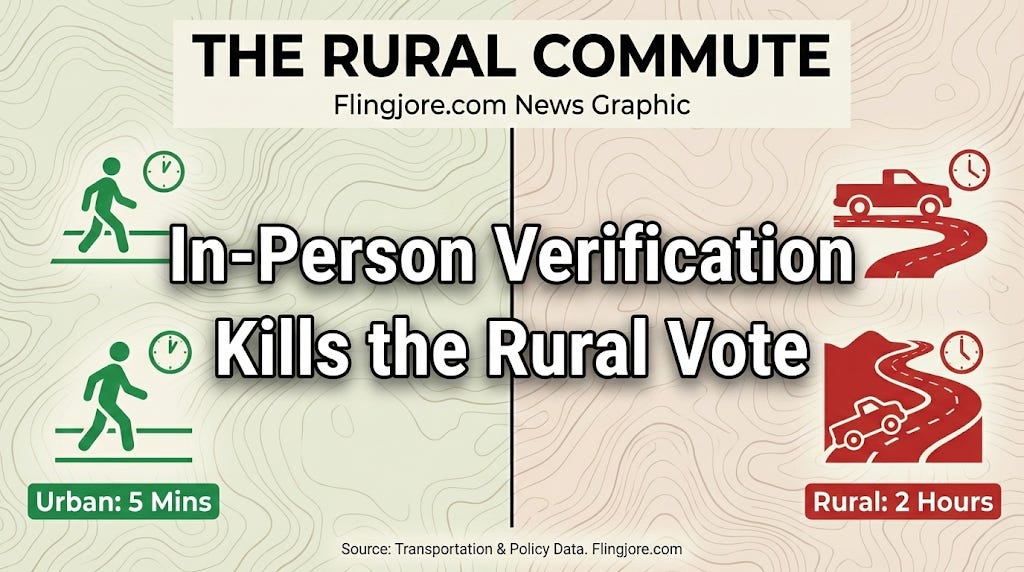

Move west to the “T” of Pennsylvania — deep red country where Trump won upwards of 70% of the vote. In counties like Tioga or Potter, the In-Person mandate of the SAVE Act hits a geographical wall.

The county seat of Wellsboro (Tioga) or Coudersport (Potter) can be an hour-long drive for residents in the far corners of the jurisdiction.

A round trip to the election office to show a birth certificate is not a lunch break errand; it is a half-day off work. For a voter earning hourly wages, the cost of gas plus lost time effectively creates a modern poll tax of roughly $100.

These are the very voters Republicans need to “run up the score” to offset Democratic votes in Philadelphia. By making it harder for them to register or update their registration after a move, the SAVE Act suppresses the rural margins essential for statewide victory.

Wisconsin and the margin of error

In Wisconsin, which President Trump won by a razor-thin 0.86% margin in 2024, the SAVE Act collides with a unique feature of state election law: the “Indefinitely Confined” status.

The path to victory in Wisconsin runs through the WOW counties (Waukesha, Ozaukee, Washington). These suburban strongholds are aging. Many reliable Republican voters here utilize the “indefinitely confined” status, which allows elderly or infirm voters to receive absentee ballots without providing standard photo ID, let alone documentary proof of citizenship.

The SAVE Act’s rigorous federal standards could override these state-level accommodations. If thousands of elderly voters in nursing homes in Waukesha are suddenly required to produce birth certificates — documents that may have been lost decades ago — the “suspense list” in these critical counties could balloon, freezing out the most reliable voting bloc the party possesses.

Wisconsin’s election system is highly decentralized, run by over 1,800 municipal clerks. Unlike a centralized DMV, these town clerks often work part-time out of small offices with limited hours.

A rural voter in a township outside of Green Bay wants to register. Under the SAVE Act, they must present documents in person.

The town clerk is only open on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM.

This mismatch between federal mandates and local administrative reality creates a “friction gap” that makes voting inconvenient, if not impossible, for working-class rural residents.

Unfunded burden and the high cost of paperwork

Beyond the voter, the SAVE Act imposes a crushing weight on the infrastructure of democracy itself. Election administrators view the bill as a massive, unfunded mandate.

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), the legislation currently authorizes zero federal dollars for implementation.

States must practically reinvent their registration databases. Currently, systems are designed to record a signature and a driver’s license number. To comply with the SAVE Act, states must overhaul their backend architecture to securely store and index high-resolution digital scans of birth certificates and passports—a cybersecurity nightmare and a massive IT expense.

In Arizona, Secretary of State Adrian Fontes has warned that such technical “backroom work” represents a multimillion-dollar expense that county budgets simply cannot absorb.

The human cost is equally high. Every DMV clerk and poll worker must be retrained to act as a document forensic specialist. They must be able to distinguish a valid 1960s birth certificate from a rural Arkansas county from a clever forgery. They must understand the intricacies of name-change laws in 50 different states.

Research from Demos suggests the implementation costs will run into the millions. For “Red states” with fiscally conservative legislatures that slash administrative budgets, this creates a crisis: comply with the mandate and bankrupt the county clerk’s office, or fail to comply and face federal lawsuits.

Military exclusion, a technical betrayal?

Perhaps the most ironic victim of the SAVE Act is the American military voter. Military families are a constituency that the GOP explicitly courts, yet the bill introduces technicalities that make their participation significantly harder.

A Common Access Card (CAC) or a Veteran Affairs (VA) ID is the standard proof of identity for service members. However, neither of these federal IDs lists a place of birth. Under the SAVE Act’s strict DPOC rules, these forms of documentation are insufficient to prove citizenship.

A soldier stationed at Fort Bragg who hails from Pennsylvania cannot simply show their Military ID to register. They must pair it with a DD-214 form (discharge papers) or a birth certificate.

Military personnel move on average every 2.5 years. This means they are constantly new registrants in their jurisdictions.

The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA) has long streamlined voting for troops abroad.

The U.S. Vote Foundation warns that the SAVE Act’s in-person document requirements clash with UOCAVA protections.

If an active-duty soldier deployed overseas or across the country cannot mail in a photocopy of their birth certificate (because the bill demands original documents or strict verification), they are effectively disenfranchised.

Kansas’ warning and a lesson in history

The dangers of the SAVE Act are not theoretical; they have been tested in the laboratory of democracy. In 2013, Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach championed a state-level law nearly identical to the SAVE Act, requiring documentary proof of citizenship for all new registrants.

The results were immediate and catastrophic for voter access. Within three years, over 30,000 Kansans — roughly 12% of all applicants — had their registrations placed in “suspense” because they lacked the proper paperwork.

An analysis of these suspended voters revealed a stunning fact: 99% of them were legal U.S. citizens. They were young people moving for college, elderly voters whose birth certificates were lost and rural residents who simply didn’t have the time to visit the DMV.

In 2018, the law was struck down in federal court (Fish v. Schwab). The judge noted that while the state disenfranchised tens of thousands of citizens, it could only produce evidence of 39 noncitizens attempting to register over a 19-year period.

The Kansas experiment proved that papers-based systems are an indiscriminate trawling net that catches thousands of legal voters for every one illegal vote it prevents.

Security, chaos and friction

The debate over the SAVE Act is often framed as a binary moral choice: security versus chaos. However, for the serious analyst — and for the political strategist — the relevant framework is friction.

Elections are decided at the margins. In 2024, Donald Trump won the presidency by holding together a coalition of rural working-class voters, suburban security moms, and veterans.

The SAVE Act adds friction to the voting process for every single one of these groups.

It taxes the rural voter with travel time and gas costs.

It taxes the married woman with name-change bureaucracy.

It taxes the veteran with document redundancy.

It taxes the red-state county with unfunded mandates.

The math suggests that the SAVE Act is not a fortress for the MAGA movement but a roadblock. As the 2026 midterms approach, the Republican Party may find that in its zeal to close the door on illegal voting it has inadvertently locked out its own most loyal supporters.