U.S. is no longer the world policeman. It is the global repo man.

Analysis: Intervention in Venezuela and renewed interest in Greenland signal the end of nation building and the rise of sovereignty as solvency, where failed states are liable for seizure.

The transformation of American foreign policy is complete, and it has found its name in a slip of the tongue that history may well canonize: The Donroe Doctrine.

In a telephone interview from his West Palm Beach golf club this morning, President Donald Trump did more than just threaten the newly installed interim president of Venezuela, Delcy Rodríguez. He dismantled the last remaining scaffolding of his 2016 isolationist platform and replaced it with the ruthlessly pragmatic logic of a corporate raider.

The Donroe Doctrine is not about spreading democracy or stopping endless wars; it is about the acquisition of distressed assets.

The President’s stark warning to Rodríguez—that she faces a fate “worse than Maduro’s” unless she submits to U.S. management—reveals the mechanics of this new era. The United States is no longer the “World Policeman” enforcing international law, but rather the Global Repo Man, seizing collateral from owners it deems negligent.

Sovereignty as solvency

The pivot centers on a fundamental redefinition of sovereignty. For centuries, the Westphalian system relied on the idea that a nation’s borders are inviolable, regardless of how poorly it is run. The Donroe Doctrine introduces a caveat: Sovereignty is a privilege of solvency.

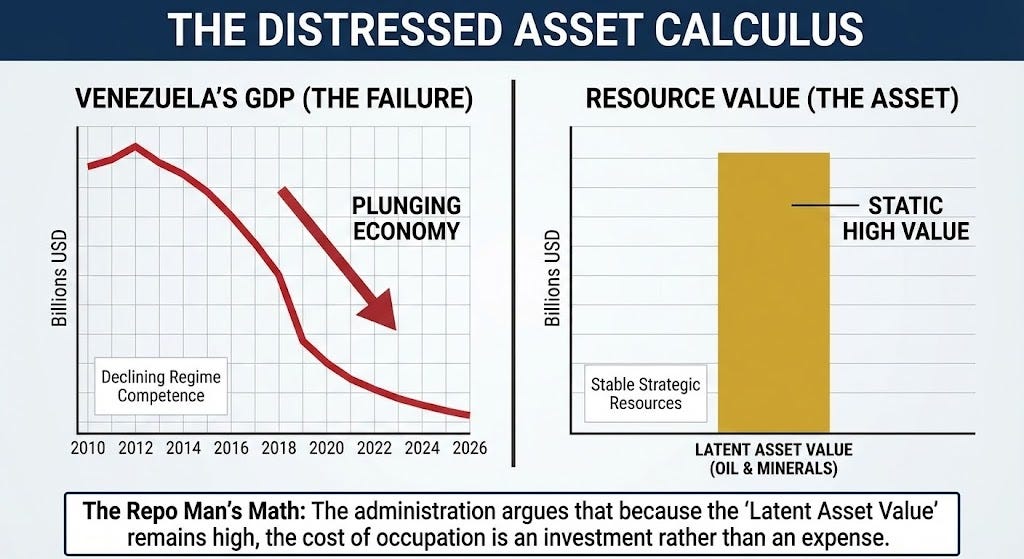

”The country’s gone to hell. It’s a failed country,” Trump said in the interview, justifying the intervention not on humanitarian grounds, but on management grounds. In the language of high-stakes real estate, Venezuela is a building with good bones—specifically vast oil reserves—but terrible management. The solution, therefore, is not to lend the landlord money or sue him with sanctions, but to evict him and take the keys.

This utilizes a sort of political physics: just as nature abhors a vacuum, the Donroe Doctrine posits that a vacuum of competence creates a gravitational pull for intervention. This explains the otherwise baffling contradiction between Trump’s 2016 rhetoric and his 2026 actions. He campaigned against the Iraq War because it was a bad investment, a “money pit” with no tangible return. Conversely, he supports the Venezuela operation because he views it as a profitable renovation, a nearby asset that can be “flipped” for value once the “bad tenants” are removed.

The Greenland ‘tell’

The President’s casual pivot to Greenland during the interview serves as the strategic “tell.” When he stated, “We do need Greenland, absolutely,” immediately after discussing the capture of Nicolás Maduro, he linked two seemingly disparate geopolitical flashpoints into a single portfolio.

To the “Donroe” mindset, Greenland and Venezuela are entries in the same ledger. One is a strategic acquisition for defense, the other for resources. The fact that one is an autonomous territory of a NATO ally and the other is a sovereign South American republic is a distinction that matters less than their status as “under-utilized” assets in the American hemisphere.

This approach represents a “civilizational erasure” of the nuances that usually govern diplomacy. The cultural and political identities of these nations are secondary to their physical utility. It signals an end to the End of History nostalgia, where the West believed liberal democracy would naturally spread through soft power. Hard power—the power of seizure—is back.

Flipping the script on Monroe Doctrine

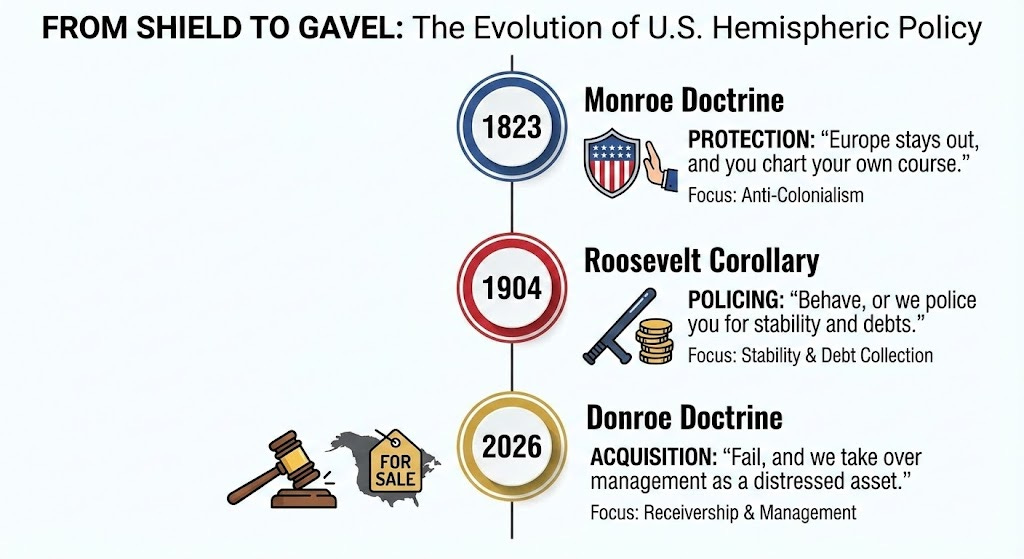

The historical irony of this moment is sharp enough to cut glass. When President James Monroe articulated his famous doctrine in 1823, it was essentially a “No Trespassing” sign aimed at Europe.

Its stated purpose was anti-colonial: to protect the newly independent Latin American nations from being snatched up again by Spain or Britain. The Donroe Doctrine takes that shield designed to protect sovereignty and forges it into a sword to strip it away.

While the Monroe Doctrine promised that Europe would stay out so Latin America could chart its own course, Trump keeps the exclusion zone but discards the autonomy. By asserting the U.S. will “temporarily run” Venezuela, he enforces the very foreign administration Monroe prohibited.

Historians often cite Theodore Roosevelt’s 1904 Corollary as the moment the U.S. became the hemisphere’s policeman, but TR’s “Big Stick” was largely about debt collection and stability. The “Donroe Doctrine” goes further. It is not just policing; it is receivership.

Delcy Rodríguez’s defiant response — ”We shall never be a colony ever again” — shows that Caracas understands this shift perfectly. She frames the conflict not as a political dispute, but as an anti-colonial struggle against the successor to the Spanish Empire. In her view, the U.S. has ceased to be the guarantor of independence.

Liquidation sale

This moment marks the final death of the post-Cold War era. For decades, U.S. foreign policy was driven by a nostalgia for the World War II order—a belief in alliances and international norms. The “Donroe Doctrine” has no nostalgia and no sentimentality. It looks at the map of the Americas and sees only liabilities and assets.

As Secretary of State Marco Rubio noted, when Trump sees a problem, he addresses it. In this new framework, the “problem” is not tyranny; it is failure.

The question is no longer whether the U.S. can “fix” Venezuela, but whether the rest of the hemisphere views this as a liberation or a liquidation sale.

If the doctrine holds, no “failed” nation in the Americas is safe from the repo man.

Repo-man, indeed, to possess all the world, OMG😟things are just getting better and better and I mean that sarcastically, by all measures imaginable that can be mustered by the democratic party and the voters that need to vote big time for them to help them, we need to defeat Trump and his party or there will be soon down the road nothing left